By Ravinder Singh Robin

New Delhi , August 4, 2025

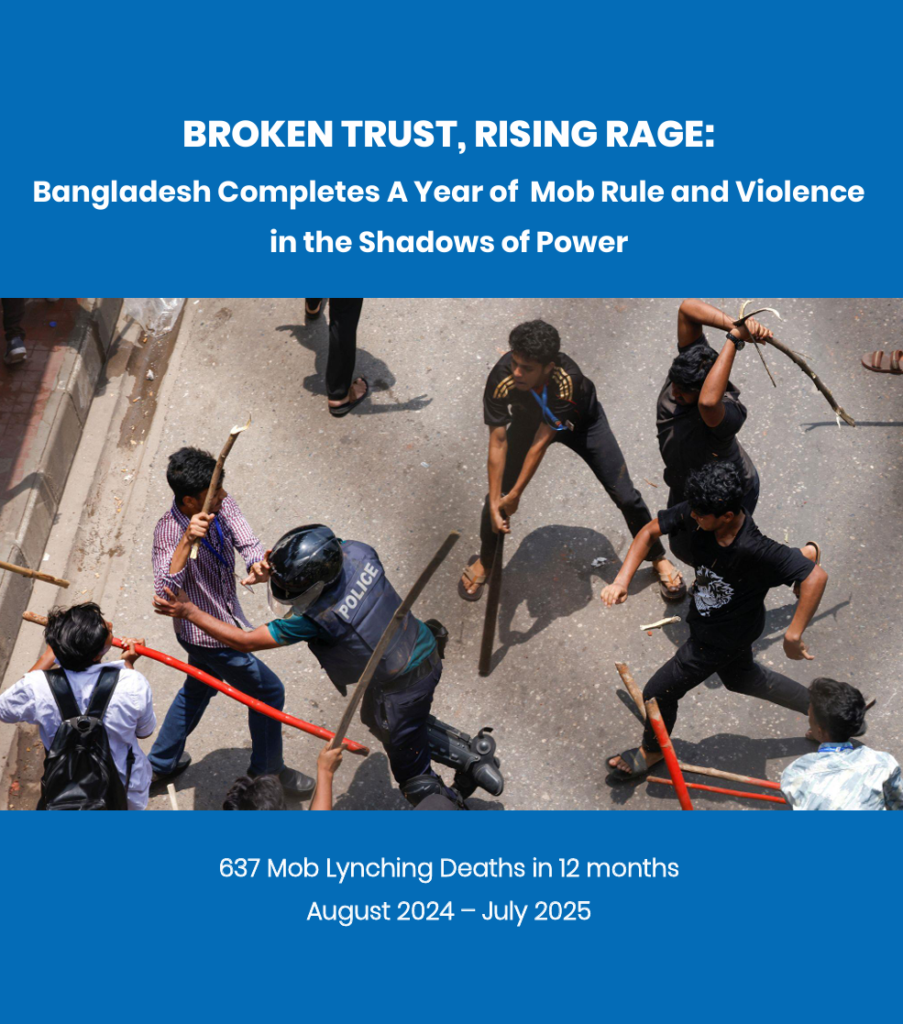

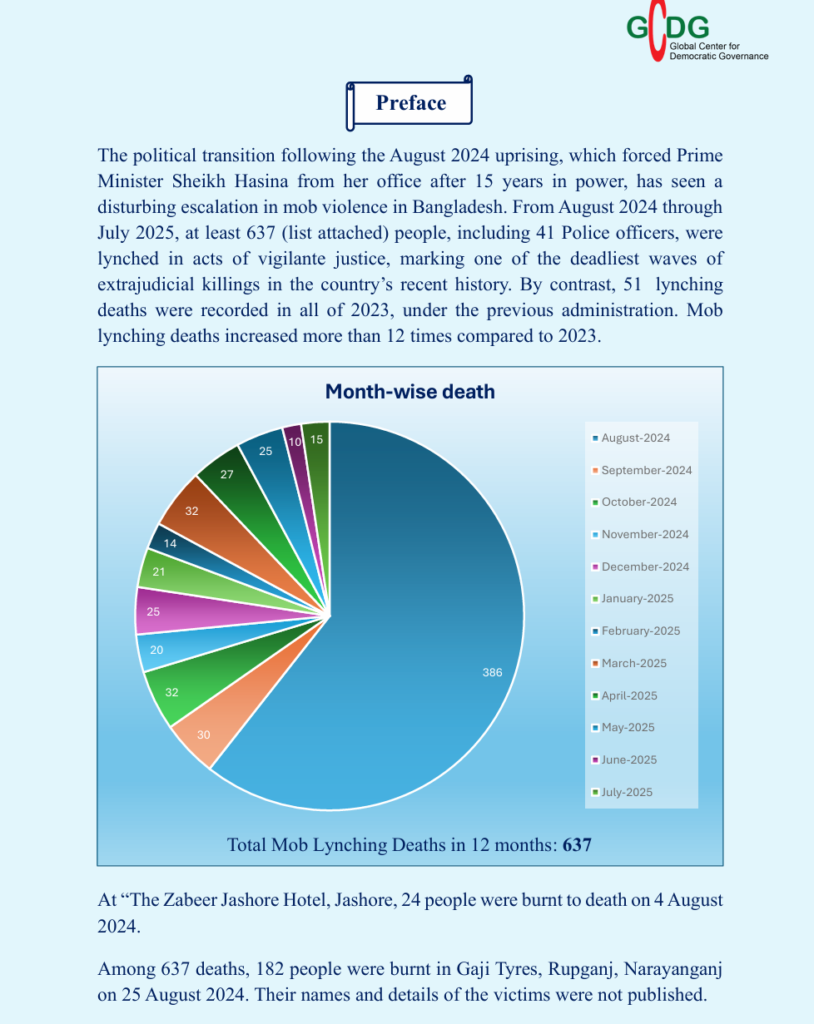

The landscape of Bangladesh has been dramatically reshaped in the twelve months since the August 2024 uprising, which saw Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina ousted after 15 years in power. In the political vacuum that followed, the nation has witnessed an alarming surge in mob violence, with at least 637 people, including 41 police officers, killed in mob lynchings from August 2024 to July 2025—a stark escalation compared to 51 such deaths the previous year.

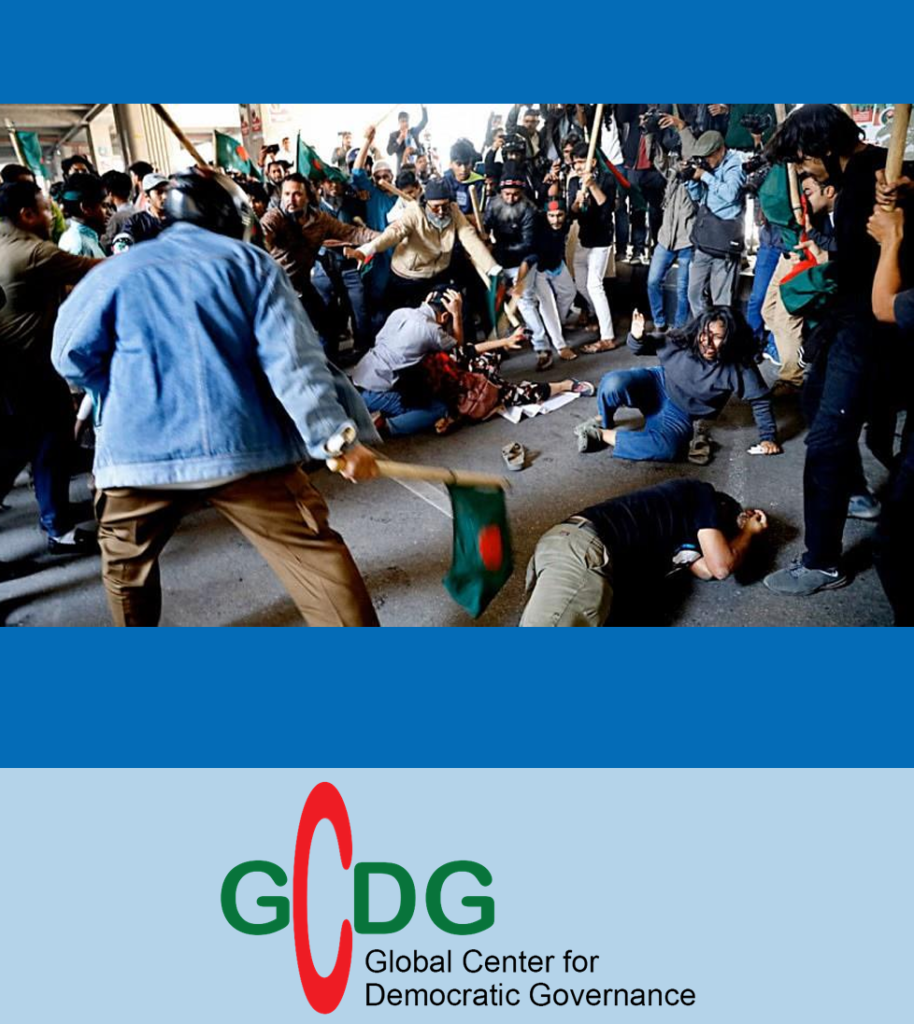

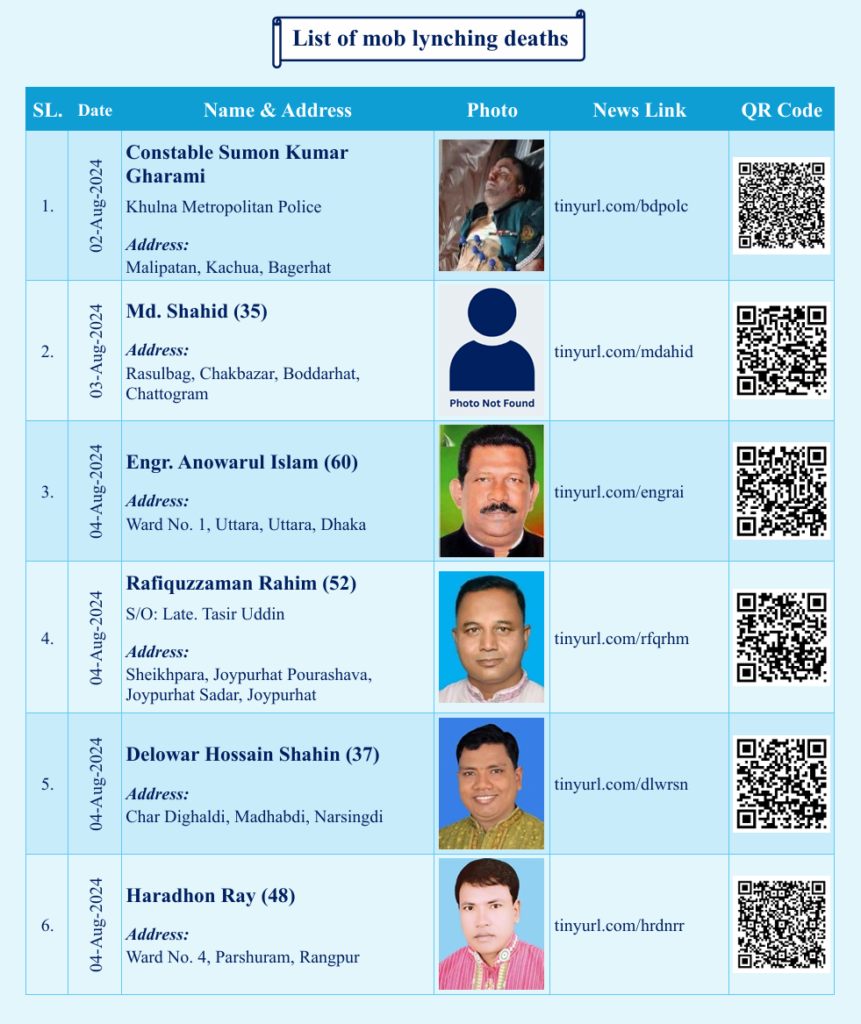

A recent report by the Global Center for Democratic Governance (GCDG) outlines a deadly wave of extrajudicial killings, marking this period as one of the most violent chapters in modern Bangladeshi history. Most victims fell prey to vigilante justice, fueled by rumors, political resentment, or suspicion, as the weakened justice system failed to uphold the rule of law. Public spaces, once considered safe, have devolved into flashpoints for mob killings, often sparked by little more than accusations of theft, harassment, or blasphemy12.

The forensic reality is both staggering and sobering: In a single month, 386 deaths were recorded, with incidents ranging from public burnings at hotels to the targeted killing of minority and religious figures such as the lynching of Hindu social worker Lal Chand Sohag, livestreamed to a horrified nation. The rise of smartphones and social media has compounded the crisis, enabling rumors to incite deadly violence within minutes, as evidenced by the deadly attack in Chattogram after false claims circulated online3.

The interim government, led by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, has vowed “zero tolerance” towards vigilante attacks and launched legal awareness campaigns, but arrests and convictions remain rare. Critics contend that the government is more focused on consolidating political power and neutralizing remnants of the previous regime than restoring judicial order. National surveys mirror the despair: 71% of Bangladeshi youth now consider mob violence a regular aspect of public life, with nearly half fearing politically motivated attacks4.

Following her ouster, Sheikh Hasina sought and was granted asylum in India, a move that has introduced complex dynamics into bilateral relations. India’s humanitarian gesture is seen as both a reaffirmation of historical ties and a pragmatic step in regional stability, but it has also drawn criticism from sections within Bangladesh’s new administration, who view Indian involvement with suspicion.

Since Hasina’s arrival, border security and intelligence cooperation have intensified, particularly to prevent cross-border violence and manage refugee inflows. While official rhetoric from both sides emphasizes cooperation, there is a subtle strain in diplomatic engagements. India remains cautious, balancing its support for Hasina with the necessity of engaging Bangladesh’s interim government. The situation has injected a note of uncertainty into trade negotiations and water-sharing agreements, as Dhaka seeks to assert its independence amidst ongoing turmoil.

As Bangladesh marks a year since the upheaval, the question looms: can it reclaim the rule of law, or will mob justice become an entrenched facet of its national life? For many, fear and silence dominate, a testament to the deep scars left by a year in the shadows of power. eom